Posted August 8, 2025 by Martin

Core principles of how I approach narrative writing for dynamic tabletop roleplay

Let me tell you a story.

It’s 1992. I’m 12 years old. A bookish kid who loves to doodle, space battles and fantasy monsters, thoughts always off somewhere else that’s ten minutes sideways from where the rest of me is awkwardly trying to take up as little room as possible. In a small town where boys are supposed to forge friendships doing typical “boy things” (soccer, skiing, skipping stones and school), this is inconvenient. Still, I have all the friends I need: just enough to seat a table.

20-sided dice clatter across the tabletop. I’m sitting behind a cardboard screen at the head of the table. On my side of the screen, charts and rules references and lists; on the side facing my friends, glorious ‘80s fantasy art. Snacks and character sheets litter the table, but all our eyes are glued to a d20 as it bounces towards destiny. Months and weeks of play have come down to this. The fate of a small but mighty band of adventurers rests on a roll of a die.

To an outside observer, we’re huddled around a dinner table at a friend’s house, but in reality, we’re desperately seeking shelter from a deadly snowstorm high up in the Iron Sword mountains. The chill of the Dragon’s Breath winds is biting with all the ferocity of their namesake. Night falls. Visibility is low. Food, as much as hope, is in short supply. By the light of a flickering torch, the party’s scout has spotted something off in the distance that might be a cave entrance. But this mountainside is treacherous, and one wrong step might kick off an avalanche that will bury us where no one will ever find our bodies. There’s a footstep’s width between salvation and calamity.

Everybody’s holding their breath as the die comes to a rest, and…

Man, I wish I could take credit for this. I wish I could sit here and tell you that even at the tender age of 12, I was already a gifted storyteller who knew how to spin a captivating yarn. But the fact is that my friends and I crafted this story together; at the end of the day, this experience of shared emergent narrative is the fundamental draw of tabletop role-playing gaming. Call it living out a power fantasy, escapism, improv with dice, or whatever, but if you strip it all back, this is our hobby’s marrow.

I’m not going to claim that I’ll teach you how to write the next great role-playing campaign. But over the course of 30-plus years, I’ve learned techniques, concepts, and best practices for how to craft collaborative narratives that will open up play at your table in new and exciting ways, keeping your players looking forward to the next session. If you’re new to the hobby, this guide is for you. If you’re a seasoned player in search of inspiration; if you’ve hit a wall in your writing; if you feel like your game needs something but you’re not quite sure what to do, this series of guides is for you. It’s for everyone who’s ever stared at a blank page and wondered.

Let’s roll.

When talking about role-playing games, it’s useful to consider static and dynamic narrative. (Fair warning: This first blog will be heavy on my own approach to a theory of collaborative narrative writing, but I promise that everything we establish here will serve you well in future installments. I’ll do my best to not make this a dry slog.)

Narrative writing isn’t just one thing. People have been telling stories for as long as there have been people, but for much of history, the most common form of narrative has been via static storytelling.

In a static narrative, the story is set in stone. No matter how many times you crack open your favorite book, things will always play out the same… unless your favorite book happens to be a Choose Your Own Adventure book, where the reader gets to find their own way through the story and may end up at a number of different endings. This kind of story where events and outcomes change depending on audience choices is an example of dynamic storytelling.

Static and dynamic storytelling aren’t a binary; they exist on a spectrum. In a Choose Your Own Adventure book, the number of decisions and outcomes is limited by what’s on the page. Sometimes, different choices lead to the same outcome as different story paths converge. Even in a classic book, deliberate ambiguity can allow the reader to interpret the same passage in different ways. And each time you tell a story to your friends, you embellish and tweak things to match your audience’s energy.

No narrative is truly static, and no narrative is truly dynamic. But each storytelling medium favors one type over the other, and this informs how you’ll craft an effective narrative in a given context. Due to the highly collaborative nature of tabletop role-playing games (TTRPGs), this medium is perfect for dynamic, collaborative storytelling. The game master (GM) may be at the head of the table, but the story is being told by all the players in the room together.

As outlined above, in theory TTRPGs should sit at the far, far end of the static-dynamic storytelling spectrum. But in practice, even the most flexible GM can’t accommodate each of their players’ whims. And as we’ll see later, placing limits on what players can and can’t do helps create more compelling narratives, because this makes player choices more meaningful. I’m going to call the limits within which players make choices the decision space.

How exactly does limiting player choices make for more meaningful decisions? Let me give you an example.

Say you’re playing a steampunk wild west fantasy game. The party is on a train escorting a team of geomancers and alchemists working for Lone Star Mining Corp to the company town of Providence Flats, where they’re tasked with dowsing for valuable minerals. But, oh no, the train is hijacked by Los Muertos, a gang of undead bandits here to abduct the head alchemist! To make matters worse, the train is headed for a bridge that has been collapsed by Los Muertos as a distraction. Now the party has to make a choice: jump onboard the decoupled rear car and focus on stopping the bandits (sacrificing everyone else aboard), or head for the engine and try to save everyone aboard the train (but letting the bandits get away), or split up (and drastically reduce their chances at succeeding at either task)?

Here, decision space has been limited by a number of factors:

If decision space is too constrained, players will feel like they aren’t able to make decisions; this kind of overconstraining is also known as railroading. If it’s too relaxed, players will feel like their decisions don’t matter. I deliberately chose an example narrative set on a train to talk about railroading to illustrate a point: don’t be afraid of constraining player choices, as long as you do so in a way that lets the players act out their characters in a way that aligns with their motivations, goals, and drives. If you keep running into situations where players try to break out of the decision space you’ve set up, that’s a sign you’re probably constraining them too much. Conversely, if your players feel aimless and sessions are spent meandering, then you can try to tighten their decisions space a bit more. Players checking their phones at the table are a sign you need to recalibrate, and I always start by looking at how I’m handling decision space.

One of the GM’s key functions is to manage decision space.

If players feel like they are free to make decisions and that those decisions have a meaningful impact on the narrative, they experience agency. Think of agency as the opposite of railroading. Most of the time, a well crafted narrative will try to optimize agency to keep players engaged, though there are instances when deliberately restricting agency can also be a powerful storytelling tool.

When you think about what constraints define decision space in a TTRPG context, those constraints fall into one of two categories: narrative constraints, and mechanical constraints.

Mechanical constraints emerge from the game’s rules. For example, a player may want to put an arrow clean through the super mutant leader’s eye and eliminate that threat in one fell swoop, but even with a perfect roll of the dice and all the criticals in the world she won’t be able to one-shot the boss because her weapon doesn’t do enough base damage. Narratively, that’d be a very cool character moment, but the game mechanics simply don’t allow it.

In this case, the player can still choose to carry out the attack, but the outcomes of that choice have a hard limit. Mechanical constraints tend to limit outcomes more than they limit actions, though they do also limit actions.

Narrative constraints are the limits that emerge from your storytelling. Suppose the players find themselves in a mine shaft that’s slowly filling with noxious gasses and lava. Mechanically there’s nothing stopping them from setting up camp right then and there, but narratively that’d be the end of this campaign. As the story unfolds, narrative constraints will shift and change. They are naturally more dynamic than mechanical constraints, which tend to be more static.

Typical mechanical constraints include:

Typical narrative constraints include:

TTRPGs can be arranged on a narrative vs. mechanics spectrum. On one end of this spectrum, the rules are very lightweight and the intent is to create as few mechanical constraints as possible so decision space is defined mostly by narrative constraints. On the mechanics-heavy side, rules are detailed and sophisticated, creating a clearly delineated and predictable decision space held together by mechanical constraints. Sometimes this spectrum is also called “crunch,” with crunchier TTRPGs leaning into an almost simulation-like way of play where there are detailed rules and rolls for all kinds of different systems, while less crunchy games handwave the number crunching in favor of not letting dice rolls get in the way of telling a story.

Think of some TTRPGs you’ve played. Where do they fall on this spectrum, whether you look at it as narrative vs. mechanics or high crunch vs. low crunch? Which ones did you enjoy more? What’s your preferred flavor?

Communicating narrative and mechanical constraints clearly and unambiguously is another key part of what a GM does as part of managing decision space.

Alright, that’s enough theory; let’s cook.

When you start outlining your narrative, whether that’s a whole campaign or just the next session, consider the decision space you’ll be creating for your players. You don’t have to anticipate every idea they’ll come up with; players will always find a way to do something so out of left field that no amount of planning could have prepared you for it. If you try to guarantee a specific outcome, you run the risk of railroading. But if you think about the narrative in terms of the decision space it takes place in, taking into consideration what narrative and mechanical constraints you’ll put in place, that allows you to set up a scenario where players can act with maximum agency while still playing out a coherent and engaging story.

Try to answer the following questions when deciding on your narrative’s decision space:

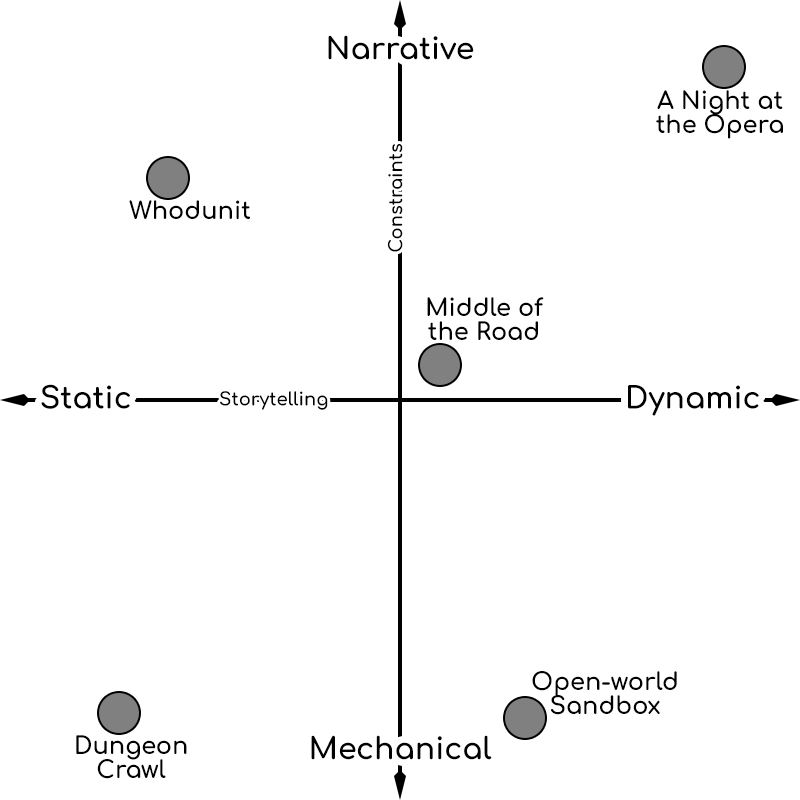

Using these dimensions, we can identify certain broad types of TTRPG narrative species.

Dungeon Crawl: A classic TTRPG adventure where the party explores a dungeon room by room, fighting monsters along the way, collecting loot, and eventually facing a boss encounter at the end. These are mechanics-first narratives with fairly static stories. Lots of dice rolling, comparing stats, and strategy. As close as TTRPGs can get to traditional board games.

Whodunit: Your typical detective story that sees players trying to solve some kind of mystery by gathering clues, interviewing NPCs, and using their skills of deduction. These adventures put narrative over mechanics, while the overall story progresses towards a fairly predictable, static conclusion such as identifying the killer (usually the butler), recovering the MacGuffin, etc.

Open-world Sandbox: When the party is free to explore a game world at will, following a loosely defined story and mostly constrained by game mechanics more than anything else, that’s a typical sandbox.

A Night at the Opera: Intense and narrative-driven drama with a highly dynamic story. The favorite of players who love to immerse themselves in their characters and act out big personalities.

Middle of the Road: The kind of adventure that strikes a balance between narrative and mechanical constraints, with stories that offer a healthy bit of flexibility without ranging too far afield. Offers something for every type of player without hewing too far to any particular direction.

Now it’s your turn. Look at the grid above and see if you can think of any other types of archetypical TTRPG stories; where would you place them? Alternatively, what happens if you take one of the archetypes that are already on the grid and shift them by one quadrant? How does it change a dungeon crawl if the constraints become more narrative-focused instead of mechanical, for example if the dungeon’s main challenge isn’t a horde of monsters but a series of puzzles or mysteries?

Can you layer different story archetypes, and how does that affect the available decision space? For example, assume you want to segue from an open-world sandbox to a whodunit. Let’s say while exploring the wasteland, the party discovers a merchant caravan, and one of the caravan guards has been murdered. Everyone is suspicious of each other, and one of the merchants asks the party for help, figuring they’re impartial outsiders who obviously had nothing to do with the murder. Which constraints do you need to adjust, and which constraints can you carry over?

Let’s recap a few key points and concepts.

With the basics covered, next time we’ll dive into how to apply these concepts when shaping narrative Arcs, Plots, Quests, and Goals. We’ll take a look at the sandbox paradox of narrative writing and how to resolve it, and we’ll also explore how objective hierarchies can help make the game more fun for your players.

See you next week!