Posted August 13, 2025 by Martin

How to scaffold a narrative using a goal-driven approach

Picture this: You’re sitting down at a booth in the back of some drekhole in the Redmond Barrens. You spot a few familiar faces; that lady with the moss in her hair and the wild eyes is a shaman, and word on the streets is she’s good to have on your side in a firefight. That twitchy elf with the chromed-out cyberarm and the grotesque pink mohawk, not so much. What are you getting yourself into here.

Finally, an aggressively nondescript gentleman in a suit slides into the seat across from you. He’s trying to act cool, but you’ve been running the shadows long enough to smell fresh meat when it presents itself. Your immediate instinct is to bail, but you’ve got payments coming up, and it’s been made unambiguously clear to you that any further delays are going to move your relationship with your friendly neighborhood loan shark to the broken legs and smashed kneecaps stage. So you ignore your gut, stick around, and listen.

“Thank you for taking the time to meet on such short notice,” the suit begins, exposing his soft underbelly almost immediately. This is going to be a very easy negotiation. “The parties I represent have an urgent need for discreet assistance in a delicate matter, and you all came highly recommended. We’ve recently learned that Whitefin Botanicals, one of our competitors, is developing a new product. We need you to discover what they are working on.”

You look around the booth. Since no one else seems eager to jump in, you take the lead. “So is this going to be a pure matrix run then? Social engineering? Physical infiltration? That’s not gonna be cheap, omae.”

“I defer to your expertise on how to obtain the information.”

“I… see.” You don’t, not exactly. “And when do the parties you represent need this done by?”

“The sooner, the better, I’m told.” So much about that ‘urgent need,’ you note.

“How worried are you about our efforts being detected?” That gets the pink mohawk’s attention. Guess the rumors are right and she’s not a huge fan of the stealthy approach.

“Well, we’d prefer it if you didn’t draw too much attention to your activities, but ultimately you’re a deniable asset, emphasis being on ‘deniable.’”

You lean back while the math SPU implant in your head does its thing, spitting out a figure one flutter of your eyelids later. You name your price. The suit objects, as is tradition. After a brief negotiation, you arrive at a number both of you can agree on, and the suit splits.

The shaman stares intently off into space, as though there’s a presence at your booth only she can see. “Well, child. Where do we start?”

Yes, where indeed.

Did you catch that? This is how a lot of roleplaying adventures start: with the party being sent on some kind of errand, attempting to fulfill some kind of goal. Goals are the connective tissue that ties a narrative together, giving the story a concrete path (or a branching network of paths) to follow. They come in many different shapes and sizes, from very high-level goals like “save the kingdom” to the very small in scope like “bypass that airlock.”

While it doesn’t make a lot of sense to try to create an exhaustive compendium of all goals, I do find it useful to look at some of their common characteristics, and how we can use them to shape our narratives more effectively. Let’s look at the above example.

The party, a ragtag band of shadowrunners, are tasked with finding out what new product the company Whitefin Botanicals is working on. They’re given complete freedom in how they go about this, with no constraints on what methods they use, how much time they have, how much attention they draw to themselves, and no clear indication of why this information is important to their employer.

If we think about goals in terms of decision space, this is an example of a very open-ended goal with minimal constraints. Some tables relish this kind of play, and if that’s you, I won’t ask you to change a thing. It’s your table, after all. But I will suggest that there are some things we can do to make goals a little more engaging without constraining your players, and ways how we can use goals to create fun, memorable, and surprising narratives.

Alright then, chummers, let’s dive in.

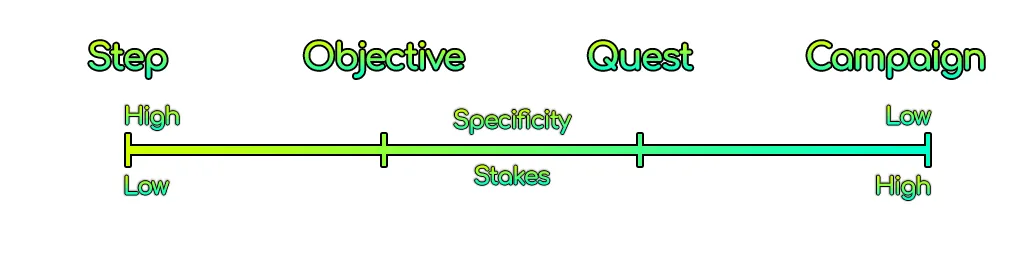

In the broadest sense, anytime players want to do something to overcome an obstacle or complete a challenge, that’s a goal. That’s an incredibly loose definition, so let’s narrow it down by introducing a hierarchy of goals that uses specific terms to sort goals by size.

There are many different ways to do this; here’s my preferred nomenclature. A Campaign is made up of Quests, each Quest has a number of Objectives, and each Objective takes one or more Steps to complete.

There’s no hard rule about what category any goal belongs to, but two useful ideas here are Specificity and Stakes. Goals higher up in the hierarchy are less specific but have bigger stakes; lower in the hierarchy, specificity increases, but stakes dwindle. Anytime you’re adding a goal to your narrative, ask yourself where that goal should land on the hierarchy. If it’s a Quest, then what are its Objectives? If it’s a Step, is it specific enough, and are the stakes appropriately low?

You may be familiar with other terms such as Quest Chain, Act, Chapter, and so on; the basic idea is to organize goals in a way that allows us to use them as scaffolding for our narrative. When you’re approaching narrative writing this way, you’ll need to decide between a top-down or a bottom-up approach.

The top-down narrative writing process starts, as the name suggests, on the Campaign level. You begin with the big idea, then fill in the rest of the Quests, Objectives, and Steps as you go. Theme plays a big role in this approach, and we’ll go into more depth on Theme in a later blog. For now, let’s just say Theme is what your campaign is “about,” the questions your narrative is exploring.

In bottom-up narrative writing, you usually start with a couple of cool things, situations, or setpieces you want to throw at your players, then construct your overarching narrative from those bits and pieces. This is a nimble and quick way to craft a story, with plenty of opportunities to build memorable moments.

Both approaches have their pros and cons, and ultimately it’s up to you to figure out which one you prefer. Know what each method’s strengths and challenges are, and how to use a Goal Hierarchy to work in either framework.

Whether you’re looking at Campaigns or Steps, every type of goal is a way to convey narrative to your players. You’ll want to be as clear as possible in how you’re communicating what each goal is asking of the players, and one way to create clarity is by using SMART goals. This concept originally comes from the world of project management, but I also find it useful in the realm of narrative writing.

A SMART goal is:

Let’s take another look at the goal set out in the introduction.

There’s some specificity there, but it’s still pretty vague. What kind of proof do the players need to produce? Is the word of one of the company’s employees enough, or should they steal full schematics? There’s no clear endstate. Likewise, it’s not clear how the players are to pursue this goal, given that their employer basically told them “You figure it out.” Also, the goal is neither relevant nor strongly time-bound.

Here’s how I would change this goal to be slightly SMARTer:

This gives a clear “what” (steal the formula), “how” (infiltrate the lab), “why” (it’s a new drug that could save lives or make someone very rich), “when” (before the shareholder meeting, presumably because somebody is planning shenanigans involving Whitefin company stock), and a well-defined endstate (return the formula to the suit).

Importantly, this still leaves room for the players to make their own choices on how they’re going to accomplish this goal. Pressure a Whitefin employee to give them an in? Use a disgruntled ex-worker to learn more about the lab’s security? Have the pink mohawk stage a diversion so the mirrorshade can do her job? Let them run wild.

Looking at goals through the lens of decision space, you ideally want the goals you set to be SMART, but not too SMART. Goals that come with too many restrictions can quickly feel like railroading, so you need to be mindful of how much you can constrain player choices. In case of doubt, try loosening one of the SMART categories and see how the goal feels afterward.

The SMART approach is most relevant to Quests and Objectives. Don’t worry too much about making every small Step as detailed as possible, and it’s okay if your Campaign-level goals have a good amount of wiggle room.

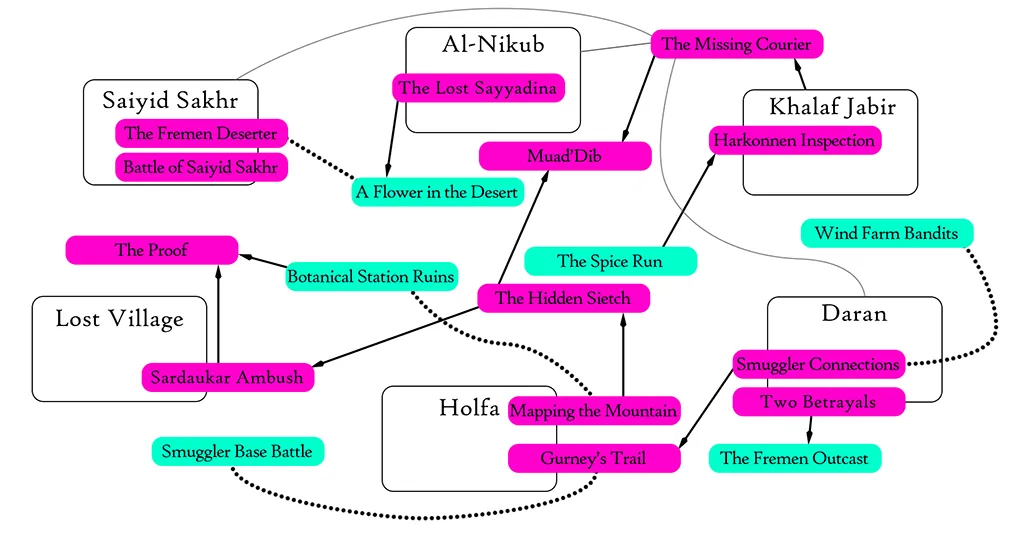

I’m a very visual person, and I find having something to look at when trying to figure out a process or a problem immensely helpful. Flowcharts and mind maps are go-to tools when working on goals, and I know many GMs who use them when they’re putting together their narrative outlines. There’s a good reason they’re so popular: flowcharts are well understood, simple, and adaptable. Many videogames use narratives that are based on flowcharts; for example, the original Wing Commander used a flowchart to map out the game’s story.

I’ve used flowcharts in the past, but one issue I see with them is that they don’t flex well. Even a deep chart can’t anticipate all player choices, and I’ve seen GMs twist themselves into a pretzel trying to keep the players within the paths laid out by their flowchart. After going through an experience like that, many GMs decide that planning just isn’t working, so they adopt an improv-heavy style where they sketch out a few ideas before the next session and just roll with whatever the players come up with.

Mind maps are popular with GMs who don’t like flowcharts. They’re a great way to organize ideas and show relationships between places, people, and situations, but they lack some of the directionality and structure of a flowchart.

Again, if that’s you, I’m not going to ask you to change; I know how much fun improv roleplaying can be. Your table, your style. But what I would like you to do is consider checking out what I’m calling a Narrative Map.

Narrative Maps combine the best parts of flowcharts and mind maps. To me, a flowchart is like an algorithm that follows a predictable if-this-else-that pattern, and like algorithms, flowcharts tend to crash if they encounter an unexpected input. A mind map, on the other hand, allows you to move freely along the association lines between its nodes, giving you a much more relational view of the narrative space. In a Narrative Map, I try to combine both.

I like to construct my Narrative Maps on the Quest level of the goals hierarchy. In the above example, I started by laying out the different locations my players would be visiting. The idea was that players could go to these places in whatever order they wanted, and the Quests would impact each other based on where they had and hadn’t visited previously. With the locations in place, I then added in the Quests for each location, adding relationships between places and quests as needed. This allowed me to come up with a tight, setting-appropriate narrative while still being able to adapt to my players’ actions and choices throughout the campaign.

Arrows represent quest sequences; one Quest usually follows another. Dotted lines represent Quests that influence each other, either by changing NPC dispositions to the characters or effecting some other change on the decision space. The thin paths indicate a Quest related to several different locations.

Earlier, I talked briefly about how important it is not to overconstrain a goal’s decision space. The idea is to preserve as much player agency as possible while still giving the narrative a strong enough structure that everyone at the table feels like they’re invested in the story. But there’s a lot more nuance to the relationship between goals and decision space, so let’s take another look.

To recap, decision space is defined by the narrative and mechanical limits of what players can do. That means the goals players pursue will always be constrained by the available decision space as well, since those goals depend on actions taken by the players. However, interesting things happen when goals are placed outside of decision space.

Decision space constrains goals, but you can use goals to modify and change decision space. For example, the presence of a team of bodyguards may prevent the party from sneaking aboard the yacht of a wealthy merchant. This is a narrative constraint on the players’ decision space. An objective goal could be to create a diversion to draw the bodyguards away from the yacht, therefore opening up the decision space to allow the players to sneak aboard.

At the table, this kind of interplay between decision space and goals is a great way for a “No, but…” kind of interaction. Anytime players succeed in turning a “No” into a “Yes” by reshaping the decision space, that increases agency. Be aware of this relationship, and always look for opportunities to let your players use goals to affect their decision space.

One final ingredient in our narrative soup is the spice that really brings out the taste in a goal: conflict.

Most goals, especially Quests and Campaigns, should have something pushing back against the players. The higher up in the hierarchy of goals, the stronger those headwinds should be. This can be something as simple as an obstacle to overcome, or it can be the story’s main antagonist or one of their proxies actively working to thwart the players. Either way, conflict should factor into how you lay out your goals.

Broadly speaking, we can group conflicts into two categories: external opposition, and internal opposition. External opposition is usually things like obstacles, while internal opposition most often takes the form of limitations and contradictions.

External Opposition:

Internal Opposition:

This list could be extended ad infinitum. The point is that opposition makes goals more interesting by presenting players with a challenge to overcome, either by overcoming some kind of external obstacle or resolving some type of internal conflict.

The trick to designing a good conflict is that whatever obstacle you’re throwing at your players should also follow the SMART template:

Think on how you can vary external and internal opposition to create interesting conflicts. Conflicting goals can be an interesting narrative element, for example. Consider the run on Whitefin Botanicals; what if it turns out that the medicine the company has been working on requires some kind of unholy magical procedure involving blood sacrifice to work?

The players might have to decide between providing their employer with the formula as requested, thereby aiding in the proliferation of vile blood magic, or they might decide to destroy the formula and permanently silence the blood mages who developed it. Of course, that might put the runners on the radar of a local coven, creating further opportunities for opposition and conflict down the line…

Now that we’ve established a baseline, let’s see how we can use our understanding of goals to and everything else we’ve learned here to construct a basic outline of a goal-driven campaign.

I’m currently working on a campaign in the Fallout universe, using the Fallout TTRPG by Modiphius. I’ll start with a top-down approach, using some of my campaign’s core themes to start building a narrative.

“War” is a core theme of Fallout, with a theme statement of “War never changes.” War, large-scale conflict, will feature prominently in this campaign. Another theme I think would fit well with this particular system is “Survival,” and a statement such as “Live together, die alone” speaks to me. Finally, I want “Exploration” to be a theme, exploring the idea of “Curiosity’s reward is growth.”

I’ll explore Theme in more detail in a later blog, but for now, we’ve got themes of War, Survival, and Exploration. That gives us a good starting point.

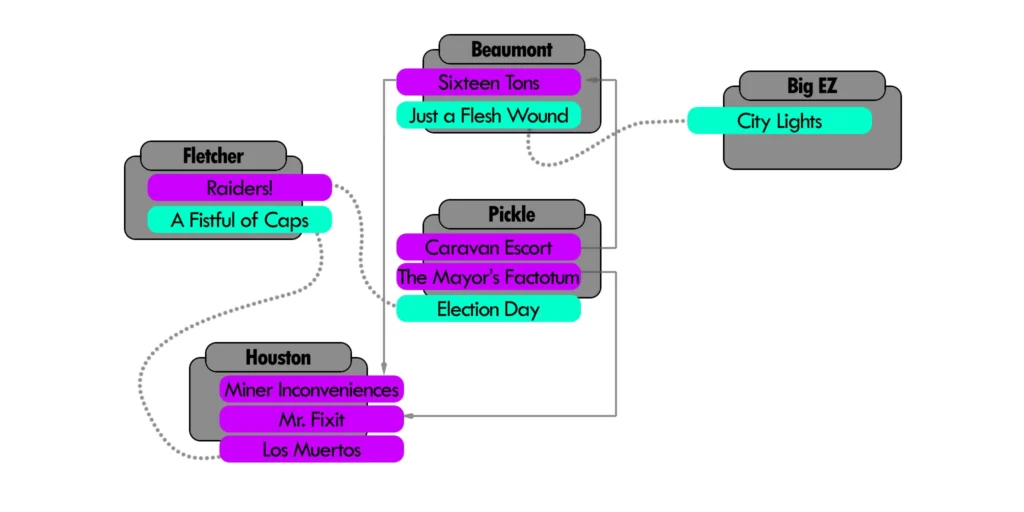

Next, I’ll start drawing up my narrative map. The campaign takes place around the Gulf of Mexico, called the Gulf of Liberty in my game. The players will start in a small post-apocalyptic town called Pickle, near the irradiated, bombed-out ruins of Dallas and Houston. Other key locations include New Orleans, here referred to as Big-EZ, the rebuilt ruins of Atlanta now known as New Atlantis, the eerie remnants of a pre-war theme park near Orlando called Futureworld, and finally Miami.

The campaign-level goal will be “End the war between New Atlantis and the Knights of the Burning Cross by any means necessary before the Gulf of Liberty is consumed by the all-devouring menace of Vault Tec’s Project S.H.R.I.K.E.” Remember our SMART goals:

This ties together the themes of War, Survival, and Exploration. Now I drop in some quests around Pickle to get the players out and about. Maybe Pickle depends on trade and good relations with neighboring survivors; that would dovetail with the campaign’s theme of “Live together, die alone.” A Quest to escort a caravan to nearby Beaumont makes sense, with a SMART goal of “Escort Obediah’s caravan and make sure at least three pack brahmin make it to Beaumont to deliver Pickle’s promised trade goods and maintain peaceful relations between the two towns.”

Let’s also add another Quest to scavenge for vital supplies in the ruins of Houston. Maybe the players learn that Beaumont’s mine could be reopened with equipment found only in that irradiated hellscape, and since “curiosity’s reward is growth” that could benefit both Pickle and Beaumont. An appropriate SMART goal could be “Venture into Houston and transport the drill actuator from the Poseidon Energy labs back to Beaumont to help reopen their uranium mine, getting in and out before the radiation kills you.” We can even add a backup Quest in Pickle that also sends the players to Houston; in this case, it’ll be “Search the RobCo factory for a new motivator to fix mayor Durkins’ assistant in time for the upcoming election.”

While in Houston, the players will run afoul of Los Muertos, an enemy faction of ghoul raiders whose main base is deep in the Bone Wastes southwest of Dallas, who are in Houston looking for… something. This encounter with Los Muertos will kick off a series of events that drags Pickle into the war between New Atlantis and the Knights of the Burning Cross, putting the campaign into high gear. Sprinkle in a few more optional side quests around Pickle, Beaumont, and Fletcher that can serve as tutorial missions to familiarize my players with a new system, and I think we’re ready to roll!

We’ve learned about how and why we use goals to structure a narrative, how to organize goals in a way that makes sense, how to design SMART goals for maximum clarity, and how to use Narrative Maps to lay out Quests in a way that flows well and can adapt to how players interact with the game.

Next time, we’ll look at another important driver of narrative: characters. We’ll look at villains, allies, adversaries, and opponents, and how to use individual non-player characters as well as entire factions to tell stories.

Until next time!